Every time you buy something new, like a phone or laptop, you're always eager to test it. The same energy should be directed to testing your circuit board.

So your circuit isn't working. Maybe the LED won't light, the motor won't spin, or the whole thing just sits there doing nothing while you question your life choices. Before you panic (or throw it across the room), let's systematically figure out what's wrong. Testing a circuit board is part detective work, part electrical engineering—and with the right approach, you can track down most problems.

Why Test Circuit Boards?

Testing isn't just for when things break. It's essential at multiple stages:

During manufacturing: Catching defects before products ship saves money and reputation.

After assembly: Verifying that you built the circuit correctly before powering it up can save you from magic smoke.

Troubleshooting failures: When something stops working, testing helps identify the culprit.

Preventive maintenance: Regular testing catches degradation before complete failure.

Essential Testing Tools

You don't need a $50,000 test lab. A few basic tools will handle most situations:

Digital Multimeter (DMM)

The multimeter is your Swiss Army knife. A decent DMM measures voltage, current, resistance, and continuity. Better models add capacitance, frequency, and transistor testing. You can find reliable multimeters for $30-100 that will last years.

Oscilloscope

For anything involving signals—audio, digital data, PWM—you need to see waveforms. Entry-level digital scopes start around $300-400 and open up a whole new dimension of troubleshooting. A scope shows you not just IF a signal exists, but its shape, timing, and quality.

Power Supply

A bench power supply with adjustable voltage and current limiting is safer than wall adapters. Current limiting protects your circuit from catastrophic shorts—if something's wrong, the supply limits current instead of letting components burn.

Magnifying Glass or Microscope

Many problems are visible: solder bridges, cold joints, cracked traces. Good lighting and magnification reveal issues invisible to the naked eye. A stereo microscope is ideal but even a 10x loupe helps.

Logic Probe or Analyzer

For digital circuits, a logic probe quickly shows high, low, and pulsing states. Logic analyzers capture and decode digital protocols like I2C, SPI, and UART—invaluable for embedded systems.

Step 1: Visual Inspection

Always start here. You'd be surprised how many problems are visible:

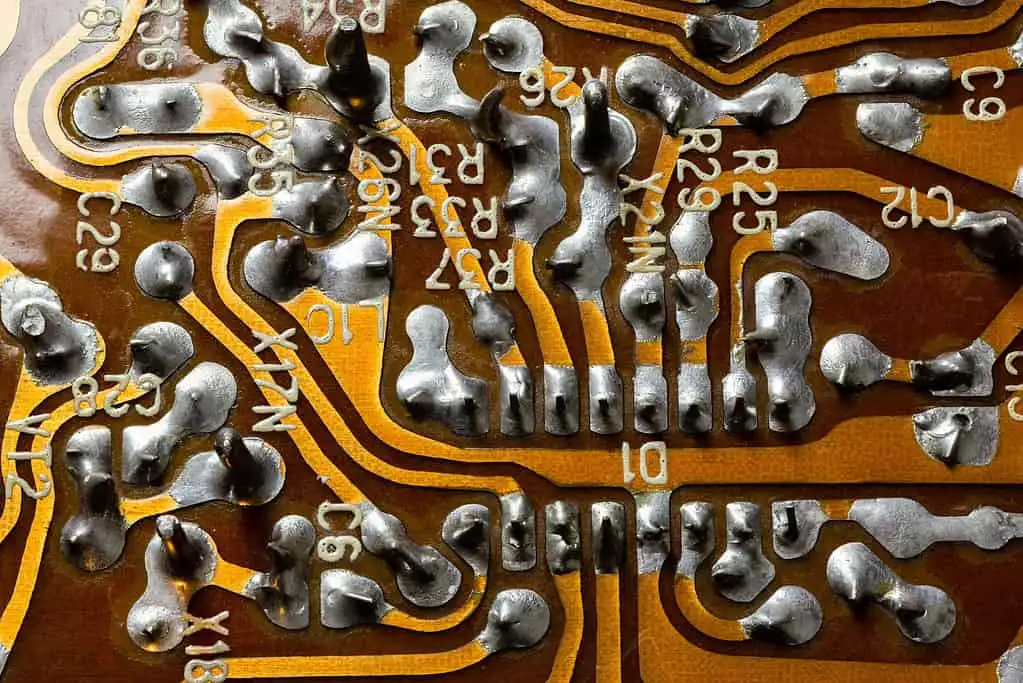

Solder bridges: Blobs of solder connecting adjacent pins or traces. Common around fine-pitch ICs.

Cold solder joints: Dull, grainy, or cracked joints that look different from shiny, smooth ones.

Missing components: Did you actually install R7? Double-check the BOM.

Wrong components: That 10Ω resistor looks a lot like a 10kΩ if you misread the color bands.

Burnt components: Discolored, cracked, or melted parts indicate overcurrent or overvoltage.

Physical damage: Cracked traces, lifted pads, contamination.

Use magnification. Seriously. Many solder issues are invisible without it.

Step 2: Power Verification

Before testing anything else, verify power is reaching the circuit correctly.

Check for Shorts Before Powering Up

With power OFF, use your multimeter in resistance mode between power and ground. You should see high resistance (thousands of ohms or more). Near-zero resistance indicates a short that needs fixing before you apply power.

Measure Supply Voltages

Power up and measure voltage at the power input, voltage regulators, and IC power pins. Common issues:

- No voltage anywhere: Power not connected, fuse blown, or dead supply

- Low voltage everywhere: Supply overloaded or undersized

- Correct input, wrong regulated voltage: Regulator issue or load problem

- Correct at regulator, wrong at IC: Bad trace or connection

Check Current Draw

Excessive current often indicates shorts. If your 100mA circuit is drawing 2A, something's wrong. Use a current-limited supply or inline ammeter.

Step 3: Continuity Testing

Continuity testing verifies that connections exist where they should—and don't exist where they shouldn't.

Testing Traces

Set your multimeter to continuity (beep) mode. Touch probes to both ends of a trace. A beep confirms connection; silence means an open circuit—possibly a cracked trace or bad solder joint.

Testing for Shorts

Check that traces that shouldn't connect actually don't. This is tedious but catches solder bridges and other short circuits.

Testing Vias

Multilayer boards use vias to connect layers. A faulty via causes opens that are hard to spot visually. Test continuity from one side to the other.

Step 4: Component Testing

Sometimes the problem is a single bad component.

Resistors

Measure resistance with the component in-circuit (power OFF). Parallel paths can affect readings, so if the value seems wrong, desolder one leg and measure again. Resistors rarely fail, but it happens.

Capacitors

Capacitors fail more often than resistors. Look for:

- Bulging tops on electrolytics—a sure sign of failure

- Leaking electrolyte—sticky brown residue

- Wrong capacitance—use a multimeter with capacitance function

- High ESR—requires an ESR meter; bad electrolytics often show normal capacitance but high ESR

Diodes and LEDs

Use diode mode on your multimeter. Forward voltage should read 0.5-0.7V for silicon, ~0.2V for Schottky, ~2V for red LEDs. Reverse should show OL (open). A short or open reading indicates a failed diode.

Transistors and MOSFETs

Test the junctions like diodes. For BJTs, check base-emitter and base-collector. For MOSFETs, the gate should show high resistance to source and drain. Many multimeters have a transistor test function.

Integrated Circuits

ICs are harder to test. Check power pins for correct voltage. Look for unusual heating—ICs that get burning hot are probably damaged. For digital ICs, verify inputs and outputs with a logic probe or oscilloscope.

Step 5: Signal Tracing

This is where oscilloscopes shine. Follow the signal path through the circuit:

Input signal: Verify the expected signal is actually arriving.

Stage by stage: Trace through each circuit block. Where does the signal stop or distort?

Clock signals: Digital circuits need clocks. No clock = nothing works.

Feedback loops: Check that feedback signals reach their destinations.

Professional Testing Methods

Manufacturing environments use specialized equipment:

In-Circuit Testing (ICT)

The "bed-of-nails" approach—a fixture with probes touching every test point simultaneously. ICT verifies every component and connection, catching 98% of defects. Expensive to set up but fast and thorough.

Flying Probe Testing

Robotic probes move across the board testing points sequentially. No custom fixture needed, ideal for prototypes and small batches. Slower than ICT but more flexible.

Automated Optical Inspection (AOI)

Cameras compare the board against reference images, catching missing components, misalignment, and solder defects. Fast and non-contact.

X-Ray Inspection

The only way to inspect BGA solder joints and other hidden connections. Reveals voids, bridges, and insufficient solder under packages.

Functional Testing

Test the board under actual operating conditions. Does it DO what it's supposed to do? This catches issues that component-level testing might miss.

Boundary Scan (JTAG)

Embedded test logic in chips allows testing connections and memories without physical probes. Essential for high-density boards with limited access.

Common Failure Modes

Knowing what typically fails helps focus your search:

Electrolytic capacitors: Dry out, especially near heat sources. Often the first components to fail in aging equipment.

Solder joints: Thermal stress causes cracks. Flex causes breaks. Lead-free solder is more brittle.

Connectors: Oxidation, wear, and mechanical stress cause intermittent connections.

Voltage regulators: Overheat from excessive current or inadequate heatsinking.

ESD damage: Static discharge kills sensitive ICs. Sometimes immediately, sometimes as latent damage that fails later.

Troubleshooting Tips

Start simple: Check power and ground first. Many "complex" problems are just power issues.

Divide and conquer: Split the circuit into sections. Test each section independently to narrow down the problem.

Compare to a working board: If you have a known-good unit, compare measurements. Differences point to problems.

Check the obvious: Wrong polarity? Reversed connector? Jumper in wrong position? We've all been there.

Touch test (carefully): Components running unusually hot indicate problems. Use the back of your finger briefly—if it hurts, it's too hot.

Document everything: Write down your measurements. Patterns become visible when you have data.

Safety Precautions

Circuit testing involves electricity. Stay safe:

- Power off before connecting probes to avoid shorts

- Use one hand when probing powered circuits to avoid current through your heart

- Be careful around capacitors—they store charge after power-off

- Wear safety glasses when soldering

- Know your circuit's voltages—anything over 50V demands extra caution

Conclusion

Testing circuit boards is a skill that improves with practice. Start with visual inspection and power verification, then work through continuity, component testing, and signal tracing. Most problems fall into obvious categories once you know where to look.

The key is systematic thinking. Don't randomly poke around hoping to find the problem. Follow the signal path. Verify assumptions. Document measurements. And remember: the circuit is just following the laws of physics. It's doing exactly what the components tell it to do. Your job is figuring out which component is giving the wrong instructions.

Need Help with Your PCB Design?

Check out our free calculators and tools for electronics engineers.

Browse PCB Tools