BGA Ball Grid Array has increasingly become an integral element of SMD ICs needing high-density connections.

Look at any modern processor, graphics card, or smartphone chip, and you'll probably find a BGA package. Those hundreds or thousands of tiny solder balls hiding underneath the chip aren't just there to look impressive—they're the solution to a fundamental problem: how do you connect increasingly complex chips with ever more connections?

What is a BGA Package?

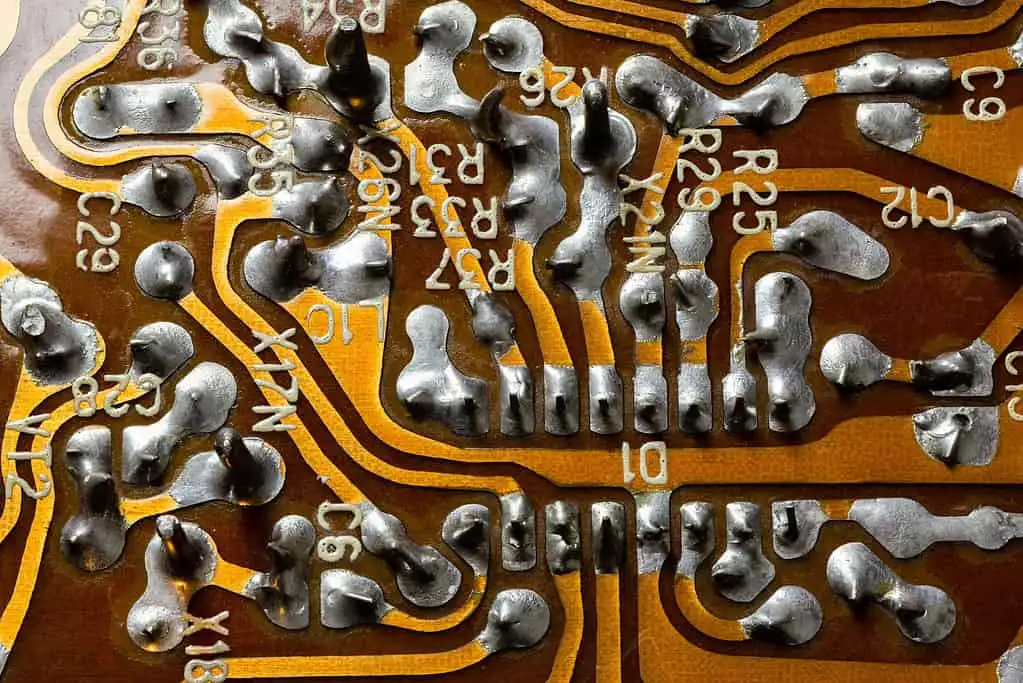

BGA stands for Ball Grid Array. It's a surface-mount package where the connections aren't on the edges (like traditional chips with legs) but arranged in a grid pattern on the bottom of the chip. Each connection point is a small sphere of solder—a solder ball.

When the chip is placed on a PCB and heated during reflow soldering, these balls melt and form permanent connections to corresponding pads on the board. It's elegant, compact, and allows for far more connections than peripheral packages could ever manage.

The technology emerged in the 1990s when chip complexity outgrew the capabilities of leaded packages. Today, BGAs are everywhere—from the processor in your laptop to the memory in your phone to automotive controllers.

Why Use BGA?

BGAs solve several problems simultaneously:

High Connection Density

A chip with 1000 pins using edge connections would be enormous. By using the entire bottom surface, BGAs pack hundreds or thousands of connections into a compact footprint. A 35mm chip can easily have 1500+ balls.

Superior Electrical Performance

Shorter connections mean lower inductance. Lower inductance means cleaner signals at high frequencies. This is why CPUs, GPUs, and high-speed memory all use BGA packaging—the electrical performance is simply better.

Excellent Thermal Properties

The array of solder balls creates multiple heat paths from the chip to the PCB. BGAs typically have lower thermal resistance than leaded packages, making them easier to cool. Some BGAs include thermal balls specifically for heat transfer.

Smaller Package Size

Without protruding leads, BGAs take up less board space for the same number of connections. The package can be close to the die size itself, enabling smaller, lighter products.

Mechanical Reliability

Solder balls are more robust than thin leads. They don't bend or break during handling like fine-pitch leads can. The connections are also self-aligning during reflow—surface tension pulls the package into correct position.

Types of BGA Packages

Not all BGAs are the same. Different applications demand different characteristics:

Plastic BGA (PBGA)

The workhorse of the BGA world. A plastic laminate substrate carries the die and solder balls. Affordable and widely used in consumer electronics, gaming consoles, and general computing applications.

Ceramic BGA (CBGA)

Ceramic substrates offer better thermal performance and electrical characteristics than plastic. You'll find CBGAs in servers, high-performance computing, and applications where heat dissipation is critical. They're more expensive but worth it when reliability matters.

Tape BGA (TBGA)

Uses a flexible tape substrate similar to flex PCB material. TBGAs are thinner and lighter, making them popular in mobile devices and wearables where every millimeter and gram counts.

Micro BGA (µBGA)

Miniaturized BGA packages with very fine ball pitch (0.5mm or less). Essential for cramming complex functionality into compact devices like smartphones and smartwatches.

Flip-Chip BGA (FC-BGA)

The die is flipped upside down and connected directly to the substrate through bumps, not wire bonds. This provides the shortest possible electrical paths and best performance. Most modern high-performance processors use flip-chip BGA.

Package-on-Package (PoP)

Stack one BGA on top of another. Commonly used in smartphones where the application processor (bottom package) has memory (top package) stacked directly on it. Maximum functionality in minimum space.

Chip-Scale Package (CSP)

The package is only slightly larger than the die itself—typically less than 1.2x the die size. Maximum miniaturization for space-constrained applications.

BGA Ball Pitch and Size

Ball pitch is the center-to-center distance between adjacent solder balls:

- 1.27mm pitch: Coarse pitch, easier to manufacture and inspect. Common in older or less dense designs.

- 1.0mm pitch: Standard pitch for many applications. Good balance of density and manufacturability.

- 0.8mm pitch: Higher density. Requires more careful PCB design and assembly.

- 0.5mm pitch: Fine pitch. Demands precision equipment and controlled processes.

- 0.4mm and below: Ultra-fine pitch. Cutting-edge applications with specialized manufacturing.

Ball diameter is typically 60-75% of the pitch. So a 1.0mm pitch BGA might have 0.6-0.75mm balls.

PCB Design for BGA

Designing a PCB for BGA components requires attention to several factors:

Pad Design

PCB landing pads should match the BGA ball size. Two approaches exist:

Non-Solder Mask Defined (NSMD): The solder mask opening is larger than the copper pad. The pad size is controlled by copper etching. Preferred because it gives more consistent pad sizes and better solder joint shape.

Solder Mask Defined (SMD): The solder mask opening is smaller than the copper pad. The mask controls the solderable area. Used when trace routing requires larger copper pads.

Routing Escape

Getting traces out from under a BGA is a routing challenge. Common strategies:

- Dog-bone pattern: Short trace from pad to a nearby via

- Via-in-pad: Via directly in the landing pad (requires via filling and planarization)

- Multiple layers: Inner layer routing for center balls, outer layers for peripheral balls

Fine-pitch BGAs with hundreds of balls may require 6+ layer boards just for routing escape.

Via Considerations

Vias near BGA pads must be carefully placed:

- Too close to pads can cause solder wicking

- Via-in-pad requires filled and plated-over vias

- Microvias and blind vias are often necessary for dense BGAs

Thermal Management

Large BGAs dissipate significant heat. Consider:

- Thermal vias under thermal pads

- Copper planes for heat spreading

- Adequate solder paste volume on thermal pads (often reduced aperture to prevent float)

BGA Assembly Process

Assembling BGAs requires precision and proper process control:

Solder Paste Application

Stencil printing deposits solder paste on PCB pads. For BGAs:

- Stencil thickness: 100-150µm typically

- Type 3 or Type 4 solder paste for fine pitch

- Proper paste volume is critical—too little causes open circuits, too much causes bridges

Component Placement

Pick-and-place machines position BGAs with high accuracy. Vision systems verify alignment. Surface tension during reflow provides some self-centering, but initial placement must be close.

Reflow Soldering

The board passes through a reflow oven following a carefully designed temperature profile:

- Preheat (1-3°C/sec to 150-180°C): Gradual warm-up to avoid thermal shock

- Soak (60-90 seconds at 150-180°C): Temperature equalization across the board

- Reflow (peak 235-250°C for lead-free): Solder melts and joints form

- Cooling (2-4°C/sec): Controlled cooling prevents stress and cracking

Nitrogen atmosphere reduces oxidation and improves joint quality.

Common BGA Defects

Even with good processes, defects occur:

Voids

Air bubbles trapped in solder joints. Some voiding (under 25%) is acceptable, but large voids weaken joints and impede heat transfer. Caused by outgassing from flux, solder paste, or moisture.

Head-in-Pillow

The solder ball melts into a pillow shape, and the paste forms a "head" that doesn't properly merge. Creates weak or open joints. Often caused by oxidation, warpage, or temperature differentials.

Solder Bridging

Adjacent balls connect, causing short circuits. Results from excess solder paste, misalignment, or ball size issues.

Open Joints

No connection between ball and pad. Caused by insufficient solder, poor wetting, or warpage preventing contact.

PCB Warpage

Heat causes the PCB to bow. If warpage is severe, corner balls might not contact their pads. Warpage increases with board size and decreases with thickness.

Cracked Joints

Thermal cycling stress or mechanical shock breaks solder joints. More common in large BGAs where thermal expansion mismatch is significant.

BGA Inspection

The biggest challenge with BGAs: you can't see the solder joints. They're hidden under the package.

X-Ray Inspection

The standard method for BGA inspection. X-rays penetrate the package and reveal joint quality. 2D X-ray shows ball presence and obvious defects. 3D X-ray (computed tomography) provides detailed analysis including void measurement.

Automated Optical Inspection (AOI)

Can verify BGA placement and inspect peripheral joints but cannot see underneath. Limited value for BGA solder joint inspection.

Electrical Testing

Functional testing and boundary scan (JTAG) verify electrical connections. Can detect opens and shorts but not mechanical quality.

Dye-and-Pry

Destructive testing: apply dye, remove the BGA, and examine the joints. Reveals joint quality but destroys the assembly. Used for process qualification and failure analysis.

BGA Rework

When a BGA has bad solder joints or the chip is faulty, it can be removed and replaced:

Pre-Bake

Moisture trapped in the package or PCB can cause damage during rework. Bake at 125°C for 24 hours before attempting rework to drive out moisture.

Removal

A BGA rework station uses hot air or infrared heating to reflow the solder while the bottom of the board is preheated. Once the solder melts, a vacuum tool lifts the BGA.

Site Preparation

Remove residual solder from pads using solder wick or specialized tools. Clean the area and apply fresh flux.

Reballing

If the BGA chip is good but needs new solder balls:

- Clean the package

- Apply flux

- Place new solder balls using a stencil

- Reflow to attach balls

Pre-formed ball arrays on tape simplify the process.

Replacement

Place the new (or reballed) BGA with precise alignment. Reflow using the rework station with careful temperature profiling.

Applications

BGAs are everywhere complex electronics exist:

Computing: CPUs, GPUs, chipsets, memory controllers—all use BGA packages for maximum performance.

Mobile devices: Application processors, memory, power management ICs, and RF chips in smartphones and tablets.

Networking: Switches, routers, and network interface chips require the high pin counts BGAs provide.

Automotive: Engine controllers, infotainment processors, and ADAS systems rely on reliable BGA assemblies.

Medical: Imaging equipment, portable monitors, and implantable devices use BGAs where miniaturization and reliability matter.

Conclusion

BGA technology is the backbone of modern electronics. Those hidden solder balls enable the dense, high-performance circuits we depend on daily. Understanding BGA design, assembly, and inspection is essential for anyone working with contemporary electronic products.

The technology continues to evolve: finer pitches, higher ball counts, advanced packaging like 2.5D and 3D integration. But the fundamental concept—an array of solder balls providing dense, reliable connections—remains as relevant as ever.

Need Help with Your PCB Design?

Check out our free calculators and tools for electronics engineers.

Browse PCB Tools