Complete guide to PCB assembly and manufacturing. Learn about SMT vs through-hole technology, the step-by-step assembly process, testing methods, and design for manufacturing best practices.

That circuit board design sitting in your CAD software looks perfect. The schematic checks out, the layout passes DRC, and the Gerbers are ready. But how does it become an actual working product? Understanding the PCB assembly process helps you design boards that manufacture smoothly and perform reliably.

This guide walks through every step of PCB assembly, from bare board to tested product.

PCB Fabrication vs Assembly: Understanding the Difference

Before diving into assembly, let's clarify terminology that often confuses newcomers.

PCB Fabrication: Creating the bare circuit board itself—the substrate with copper traces, drilled holes, solder mask, and silkscreen. You send Gerber files; you receive boards ready for components.

PCB Assembly (PCBA): Populating that bare board with components—resistors, capacitors, ICs, connectors. You receive functional circuit board assemblies.

Many manufacturers offer both services together as "turnkey" manufacturing. Others specialize in one or the other. Either way, both processes must succeed for a working product.

The Two Assembly Technologies: SMT vs Through-Hole

Modern PCBs use two fundamental component mounting approaches, often combined on the same board.

Surface Mount Technology (SMT)

Surface mount components sit directly on the board surface, soldered to pads without leads passing through holes. SMT dominates modern electronics because:

- Smaller components: 0201 packages measure just 0.6mm × 0.3mm

- Higher density: Both sides of the board can hold components

- Faster assembly: Automated pick-and-place machines handle thousands of parts per hour

- Better high-frequency performance: Shorter leads mean less inductance

Through-Hole Technology (THT)

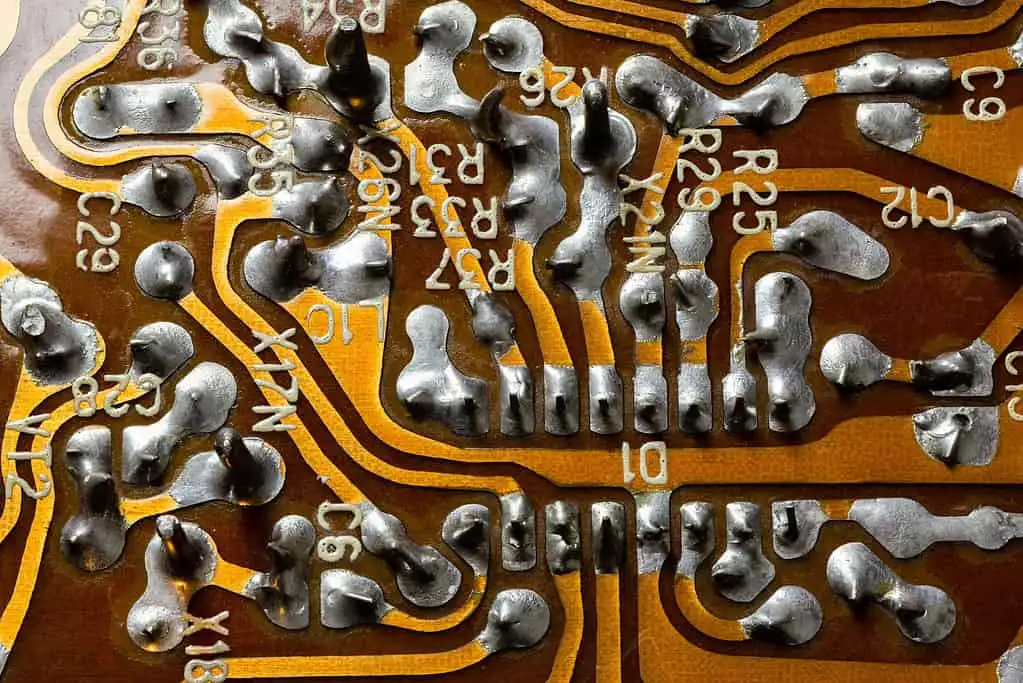

Through-hole components have leads that pass through holes in the PCB and solder on the opposite side. Despite being older technology, THT remains essential for:

- Mechanical strength: Connectors under physical stress

- High power: Components needing better thermal dissipation

- Easy prototyping: Hand soldering is straightforward

- Reliability: Military and aerospace applications demanding maximum durability

Most boards use mixed technology—SMT for the majority of components with through-hole for connectors, power devices, and anything requiring mechanical robustness.

SMT Assembly Process: Step by Step

SMT assembly follows a precise sequence that transforms bare boards into populated assemblies in minutes.

Step 1: Solder Paste Printing

The process begins with applying solder paste to the PCB pads. A stainless steel stencil with laser-cut openings aligns over the board. A squeegee blade pushes solder paste across the stencil, forcing paste through the openings onto the pads below.

Solder paste is a carefully formulated mixture of tiny solder spheres (typically 25-45 microns diameter) suspended in flux. The flux cleans oxide from pads and pins, enabling reliable solder joints.

Critical factors:

- Stencil thickness affects paste volume (thicker = more paste)

- Aperture design must match pad geometry

- Squeegee pressure, speed, and angle require optimization

- Paste temperature affects printing consistency

A good paste print is essential—most SMT defects trace back to printing problems.

Step 2: Solder Paste Inspection (SPI)

Before placing components, automated inspection verifies the paste print. 3D SPI machines measure:

- Volume: Is enough paste on each pad?

- Height: Is paste thickness consistent?

- Area: Does paste coverage match the aperture?

- Position: Is paste centered on the pad?

Catching printing defects before component placement saves the cost of processing bad boards through the entire line.

Step 3: Pick and Place

Pick-and-place machines are the workhorses of SMT assembly. These remarkable machines:

- Pick components from reels, trays, or tubes using vacuum nozzles

- Center the component using vision systems

- Rotate to correct orientation

- Place precisely on the solder paste with controlled force

Modern pick-and-place machines achieve stunning speed—placing 100,000+ components per hour. Vision systems verify correct parts and orientation, rejecting components that don't match.

Multiple placement heads and feeders allow different component types to load simultaneously. Setup time (loading feeders with correct reels) often exceeds actual placement time for small runs.

Step 4: Pre-Reflow Inspection (Optional)

Some lines include automated optical inspection (AOI) before reflow to catch placement errors while correction is still easy. A misplaced component before soldering can simply be repositioned; after soldering, rework becomes necessary.

Step 5: Reflow Soldering

The assembled board passes through a reflow oven—essentially a precisely controlled tunnel of heat. The temperature profile includes:

- Preheat zone: Gradually raises temperature, activating flux

- Thermal soak: Equalizes temperature across the board

- Reflow zone: Exceeds solder melting point (~217°C for lead-free)

- Cooling zone: Solidifies solder joints

The profile balances multiple requirements: reaching reflow temperature without thermal shock, keeping components within their temperature ratings, allowing flux to clean surfaces before solder melts, and cooling fast enough to form proper grain structure.

Lead-free solders require higher temperatures than traditional tin-lead, making thermal management more challenging.

Step 6: Post-Reflow Inspection

Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) examines every solder joint and component. Cameras capture high-resolution images, and software algorithms detect:

- Missing components

- Misaligned components

- Solder bridges (shorts between pads)

- Insufficient solder

- Tombstoning (component standing on end)

- Polarity errors on marked components

For BGA packages where joints hide under the component, X-ray inspection reveals hidden defects.

Through-Hole Assembly Process

Through-hole components follow a different path, often after SMT is complete on boards using both technologies.

Manual Insertion

For low volumes or complex assemblies, operators hand-insert through-hole components. This approach offers flexibility but depends on operator skill and attention.

Best practices:

- Follow a logical insertion sequence (low components first)

- Verify component values and orientations

- Form leads appropriately before insertion

- Check proper seating after insertion

Automated Insertion

For higher volumes, axial and radial insertion machines automatically place common through-hole components like resistors and capacitors. Specialized machines handle odd-form components like connectors and relays.

Wave Soldering

The classic through-hole soldering method sends boards over a wave of molten solder. The board passes over a continuously pumped wave that contacts the bottom surface, wetting leads and pads while solder mask prevents bridging.

Wave soldering efficiently solders all through-hole components simultaneously but requires careful setup:

- Conveyor speed affects heat transfer

- Wave height must contact leads without flooding pads

- Preheat prevents thermal shock

- Flux application ensures clean surfaces

Selective Soldering

Modern mixed-technology boards often use selective soldering instead of wave soldering. A programmable nozzle applies solder only to through-hole locations, avoiding damage to adjacent SMT components already soldered.

Selective soldering is slower than wave soldering but offers precision impossible with full-board wave exposure.

Mixed Technology Assembly

Real-world boards rarely use pure SMT or pure through-hole. The typical mixed-technology sequence:

- SMT side one: Print, place, reflow the primary SMT side

- SMT side two (if double-sided): Flip, print, place, reflow the secondary side

- Through-hole: Insert through-hole components

- Final soldering: Wave or selective solder the through-hole joints

- Inspection and test: Verify the complete assembly

Thermal budgeting becomes critical—components experience heat during each reflow and soldering step. The total thermal exposure must stay within limits.

Testing and Quality Assurance

Assembly isn't complete until the board proves functional.

In-Circuit Test (ICT)

Bed-of-nails fixtures make contact with test points across the board. ICT verifies:

- Component presence and values

- Solder joint integrity

- Short circuits

- Open circuits

ICT catches manufacturing defects efficiently but requires expensive custom fixtures for each board design.

Flying Probe Test

Instead of fixed test points, moving probes contact locations across the board. Flying probe is slower than ICT but requires no custom fixtures—ideal for prototypes and low volumes.

Functional Test

The ultimate verification: does the board work as designed? Functional test applies power and signals, verifying correct operation. This catches design errors that pass ICT and defects that electrical tests miss.

Burn-In Test

For high-reliability applications, extended operation at elevated temperature stresses components. Infant mortality failures occur early; surviving units prove themselves before shipping.

Design for Manufacturing (DFM) Considerations

Smart designers consider assembly during layout, not after.

Component Selection

- Prefer standard package sizes with good availability

- Match package thermal requirements to assembly capability

- Consider lead-free compatibility for all components

- Avoid mixing fine-pitch and coarse-pitch on the same board when possible

Pad Design

- Follow component manufacturer recommendations

- Include solder thieves for unbalanced pads (preventing tombstoning)

- Size thermal pads for proper heat dissipation during soldering

- Ensure consistent pad sizes within component families

Spacing and Clearance

- Maintain minimum spacing for stencil wall integrity

- Allow room for rework access

- Consider pick-and-place nozzle clearance

- Keep tall components away from edges

Fiducials and Tooling

- Include global fiducials for board alignment

- Add local fiducials near fine-pitch components

- Design tooling holes for fixturing

- Mark board edges clearly for depanelization

Choosing an Assembly Partner

Whether prototype or production, your assembly partner significantly affects success.

For prototypes:

- Quick-turn capability matters most

- NRE (non-recurring engineering) charges should be reasonable

- Engineering support helps catch issues early

For production:

- Capacity must match your volume requirements

- Quality certifications (ISO, AS9100, etc.) indicate process maturity

- Supply chain management reduces your logistics burden

- Geographic location affects shipping cost and communication

Common Assembly Defects and Prevention

Understanding failure modes helps you design boards that avoid them.

| Defect | Cause | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Solder bridges | Excess paste, poor stencil design | Proper aperture sizing |

| Tombstoning | Unequal heat or paste distribution | Symmetric pad design |

| Cold joints | Insufficient heat | Proper thermal profiling |

| Voids | Outgassing during reflow | Thermal soak optimization |

| Component shift | Excessive reflow temperature | Profile optimization |

The Bottom Line

PCB assembly transforms your design from concept to reality. Understanding the process helps you design boards that assemble smoothly, catch problems before they become expensive, and communicate effectively with your manufacturing partners.

Whether you're building one prototype or a million production units, the fundamentals remain the same: good design enables good manufacturing. Master both, and your products will succeed.

Need Help with Your PCB Design?

Check out our free calculators and tools for electronics engineers.

Browse PCB Tools